Resources

From expert advice and commentary to guides, reports, videos and more, dive into a wealth of industry wisdom curated by retail and merchandising specialists.

Browse resources

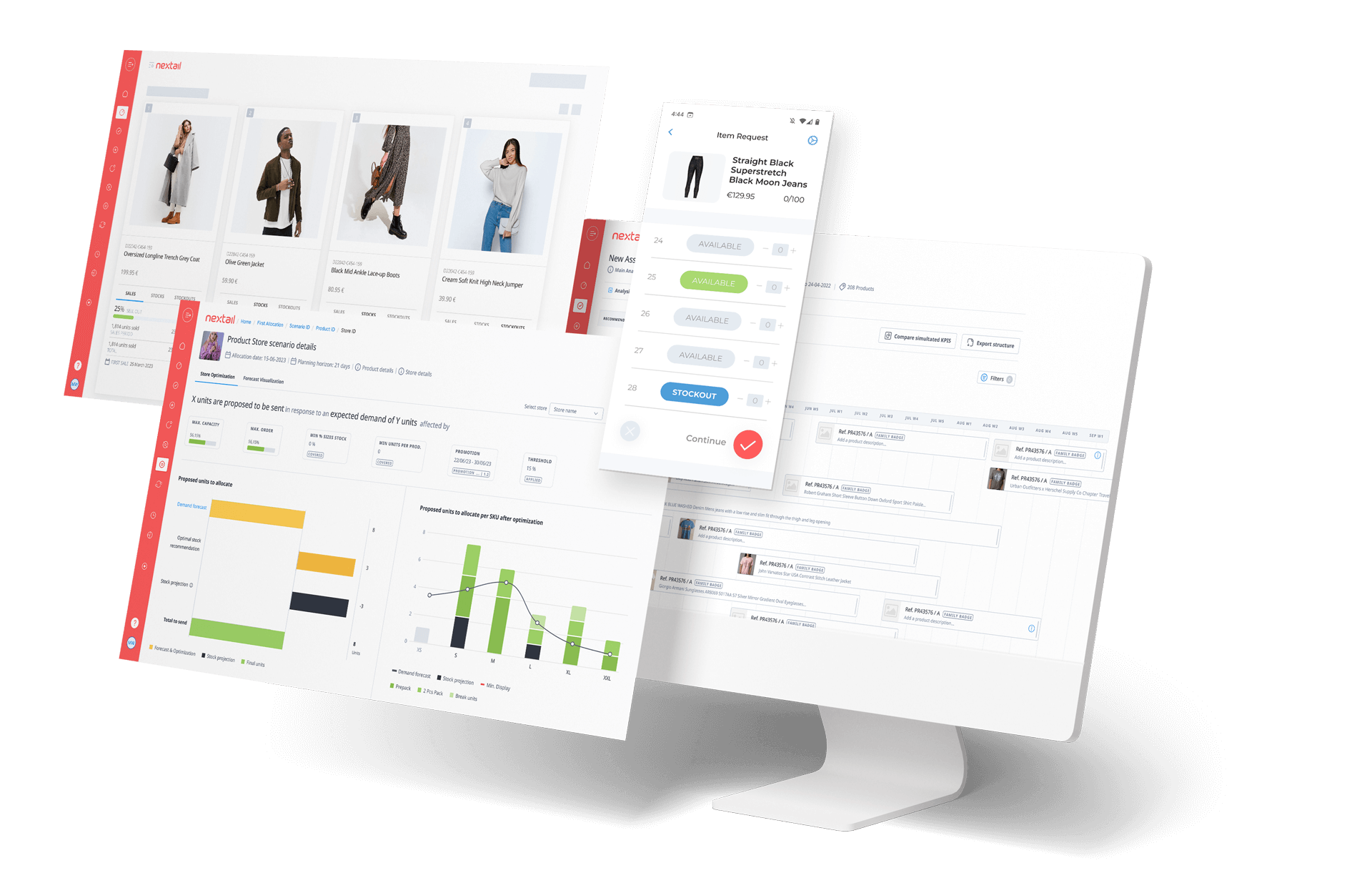

Guide

5 benefits of AI-driven inventory rebalancing

Read more

Blog

Understanding the basics: A guide to “bottom-up” hyper-local merchan...

Read more

Blog

From pain point to profit: The power of inventory rebalancing in fashion

Read more

Blog

Retail AI in 2024: 3 key takeaways from NRF’s Big Show

Read more

Blog

Inside India’s fashion retail industry with Ekta Biyani, Co-founder of Style U...

Read more

Blog

Maximizing margins: Why fashion retailers need to rethink inventory in 2024

Read more

Guide

7 considerations for selecting your next merchandise planning platform

Read more

Blog

Finding the right balance: Maximizing retail headcount and technology in fashion

Read more

Blog

The evolution of assortment planning in fashion retail: From spreadsheets to AI

Read more

Guide

RSR Guide to continuous merchandising

Read more

Blog

Why fashion retailers need to rethink the traditional planning cycle

Read more

Guide

Weekly sales, stock and intake (WSSI) guide

Read more

Blog

From guesswork to insights: Flying Tiger Copenhagen Spain enhances merchandising...

Read more

Blog

Fashion brands are choosing more female CEOs to represent them in the boardroom

Read more

Blog

Advanced retail tech picks up where WSSI leaves off

Read more

Ready to see

real results?

Let us show you how Nextail can help drive profitable growth across your entire network of stores and channels.